Being in landscape and trying to get to its very core is a physical, emotional and intellectual process that stimulates the whole mind-body connection. If that process of converging with the environment happens, the experience is felt through all the senses (sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch) and later gets connected to rationally classified observations. A landscape is never merely a conglomerate of living (plants, animals, fungi) and non-living (rocks, water, air) matter.

“There is hardly any place on earth where mankind hasn't been, and there is certainly no place on this planet that we've left completely untouched. I consider the two forces, nature and humankind, as divergent positions rather than as a unit both equipped with tremendous power.” (1)

- Interview at Valletta Contemporary, 2019

In my understanding, there are two inextricable forces that define how we perceive the complex dynamics of an environment: Firstly, the emotional (intuitive and uncontrollable) approach in which landscape becomes a space of projection that has been claimed by feelings like attachment, belonging, excitement or in some cases the negative sensation of alienation. The rational observation on the other hand is a facts-based evaluative process that takes the economic, historical, ecological and geological forces that shape an environment into account. There lingers an almost unbearable tension between the two ways of apperceiving landscape as I am naively longing to get lost in this sensual experience, but then suddenly find myself getting pulled out of this idyllic place by detecting the disturbance processes that alter the fragile ecosystem dynamics of these places.

This tension also echoes the work of Déborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro who argue that “human thought, materializes as a giant technological machine of planetary impact, effectively and destructively correlates the world”.(2) Landscape, as one part of the complex and fragile “Earth System”, cannot be considered as an independent entity and therefore is always affected by human actions.

Driven by the fact that humans have become a natural force on a geological scale – to that extend, one speaks of a new geological era (“the Anthropocene”) – I focused on the local landscape during my artist-in-residence at Leitrim Sculpture Centre and specifically the question of how humans, in collaboration with the sheep they farm, affect the Irish landscape. This impact can be seen in culturally affected areas before the obvious destruction. Like unremitting grazing machines, placed by humans in strictly defined areas, the sheep restructure the landscape by keeping the meadows open as forests and plant life yield to their cultivating patterns.

Elsewhere, the grazing of goats and sheep is regarded as an important factor in soil degradation. As the study ‘sheep and goat erosion – experimental geomorphology as an approach for the quantification of underestimated processes’(3) by geologists Ries, Andres and Wirtz points out: the process dynamics of material disaggregation and translocation is directly caused by trampling animals like sheep or goats. The amount of the material that is frequently loosened by the hooves of each animal is easily removed by wind or water.

This phenomenon became visible to me at the cliffs of Slieve League, County Donegal in cow-shaped scree patches that looked like friable wounds at the surface. Even though landscape is being constantly shaped by erosion, the effects of nature and culture come into existence in the form of completely different phenomenon. The photographic research shown as part of the solo exhibition at Leitrim Sculpture Centre NATURE, NATURE/CULTURE and CULTURE shows the distinct erosion appearances of these scarred surfaces.

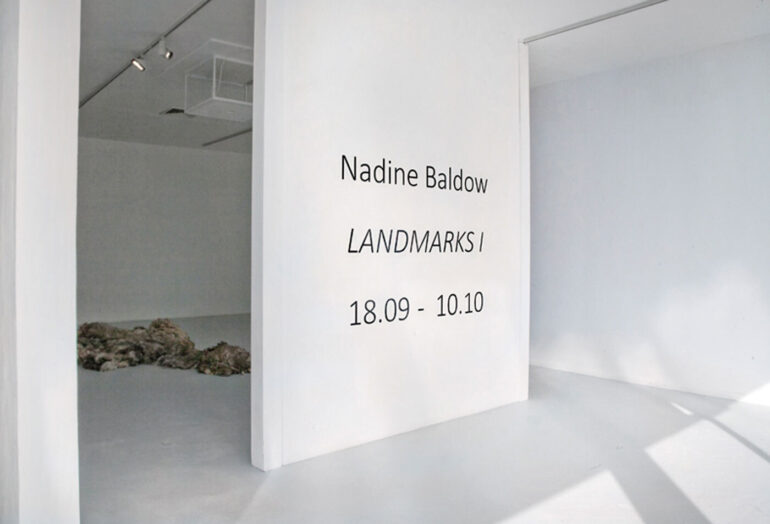

This research thematically links to the installation LANDMARKS I, which consists of more than half a ton of raw unwashed sheep wool that was treated with with spray-paint usually used by farmers to mark sheep for various classifying reasons. The quality of the material with its numerous fuzzy structures, adamant dags,(4) greasy touch and intense but not unpleasant smell is politically, ecologically and emotionally connected to the place it was found. The pressure that has been mounting on sheep farmers with the total collapse of the wool trade sticks to the materiality of the wool. Statements of the Irish Cattle and Sheep Farmers' Association (ICSA) like: “Prices have dipped as low as 5c/kg for wool that costs €2.50-€3.00 a head to shear. As a result, many farmers have been left with no choice but to dump wool over the last several months”(5) and “the current European agricultural policy has damaged the income of Ireland’s farmers“(6) make the harsh conditions caused by the worldwide expansion of capitalist economy obvious. Additionally, one might also sense the places, where the sheep have been to, by imagining them grazing on the green hills or contemplating their stress during auctions and transportations. This stratification of the animals' byproduct is placed in correlation with other works that address the interplay between human and natural systems from a geological perspective.

The ongoing series OCCUPIED OBJECTS (since 2014) imagines a future scenario in which an alien-like kind of nature occupies everyday objects. In this sense the OCCUPIED OBJECT, shown at LSC, reveals a possible dystopian outcome of humankind's story that is worth reflecting on. The relation between humans as such and their most general condition of existence imposes itself as a problem for reason, as the conditions on Earth are changing faster than we are able to adapt to them. What would a world-after-us look like?

“A (…) way of framing the opposition between life and humankind consists in projecting it into the future: life will return, invincible in its variety and abundance, reconquering the territory (the Earth) that humankind, acting like an alien, ruthless invader, had transformed into a desert of concrete, tarmac, plastic and nuclear waste”(7)

In the context of this assertion from The Ends of the World, the protagonist of Georg Steward's (1949) dystopian novel Earth Abides comes to my mind. He fails to rebuild civilization as one of the few survivors of an epidemic caused by a lethal virus – and as a consequence decides to examine how non-human life evolves after the demise of humans.

A less fatalistic approach is Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing's The Mushroom at the End of the World that looks at the diversity within the human-disturbed landscape by investigating the Matsutake, a fungi that inhabits those damaged spaces in collaborative survival within multispecies. The series OCCUPIED OBJECTS has been thematically linked to Tsing's theories by curator Maren Richter in 2019:

“In the logic of multispecies studies Baldow’s posthuman or postnature organisms do not offer necessarily a dystopian scenario only but a different scenario of how we need to look into future concepts of cohabiting the Earth.”(8)

So far, I have tried to reflect on these different concepts such as a world-without-us, a world-after-us or a world-for-man – hoping it would provoke action. Alas, this seems not enough, considering the fact that humankind is lethargically stuck in a world-wide expansion of capitalist economy and inhabiting an environment that is changing much faster than we are able to adapt to. Somehow, I believe the threat of humankind to itself is too painful to truly be processed by the human mind. We are psychologically over-challenged and rather tend to save ourselves in denial than facing the inconvenient facts. It comforts us that, though scientifically the warning signs do create an atmosphere of living in end times, there will be always some voices to tell us this is not 100 percent proven. There lingers some irony in the fact that during the current corona-crisis, one can witness the activation of immense capacities, when it comes to changing human actions on a global scale. Ecological issues, even though they are of planetary impact as well, appear less spectacular and seem to be politically subjugated.

I would love to detach myself from this world, numbing myself with the belief that I don't care what happens to every living or nonliving being on this planet. That it will be alright, because in the long term, the planet does not care if we exist. The forces of “nature” have always found a way to stabilize themselves as a self-correcting system. The shell of this attitude starts cracking the moment you fall for a place and you truly see what is really there. I sensed the remaining wilderness of that landscape. I felt its beauty and I felt its disturbance. I am facing the trouble of having affection for it and yet that makes me feel rich.

Exhibition curated by Sean O'Reilly.

Listen to Nadine talking about the show at:

“The word landmark is from the Old English landmearc, meaning 'an object in the landscape' which, by its conspicuousness, serves as a guide in the direction of one's course.”(9)

- Robert Macfarlane, 2015

- See – Valletta Contemporary, Artist Interviews: Nadine Baldow interviewed by Ann Dingli, February 2019

- Déborah Danowski, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro: The Ends of the World, Polity Press, UK, 2016, p 36.

- Sheep and goat erosion – experimental geomorphology as an approach for the quantification underestimated processes : In the presented study, the process dynamics of material disaggregation and translocation directly caused by trampling animals was quantified by means of experimental methods on test plots. Gerlach troughs were installed in order to quantify material mobilization in different directions. The slope angle and the running speed of the animals were varied. Additionally, the amount of material that was loosened by the hooves of the goats was measured.Sheep and goat erosion – experimental geomorphology as an approach for the quantification underestimated processes : In the presented study, the process dynamics of material disaggregation and translocation directly caused by trampling animals was quantified by means of experimental methods on test plots. Gerlach troughs were installed in order to quantify material mobilization in different directions. The slope angle and the running speed of the animals were varied. Additionally, the amount of material that was loosened by the hooves of the goats was measured.

- def.: clumps of dried dung stuck to the wool

- www.agriland.ie/farming-news/sheep-taskforce-sought-farmers-fed-up-of-being-political-afterthought, 21.10.2020

- www.thejournal.ie/sheep-and-cattle-farmers-are-struggling, 21.10.2020

- Déborah Danowski, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro: The Ends of the World, Polity Press, UK, 2016, p 25.

- Maren Richter: Pristine Paradise, VC Editions, Malta, 2019

- Robert Macfarlane: LANDMARKS, Penguin Press, UK, 2015

LANDMARKS I is an Artist in Residency Project and resulting Solo Exhibition by Nadine Baldow curated by Sean O'Reilly at Leitrim Sculpture Centre, Manorhamilton, County Leitrim, Ireland. All works in the exhibition were developed during the residency period in August / September 2020.

Nadine Baldow

Nadine Baldow (b. 1990, Dresden, Germany) is an artist based in Berlin whose work predominately addresses the complex relationship between “culture” and “nature” and their ongoing impact on each other. She is observing this relationship on many different levels and raises questions like: Are we still part of nature? What is 'nature' after all? Could our planet, as we ourselves have shaped it, be what 'true nature' is? The scenarios she builds through the mediums of installation, intervention, sculpture and photography could be considered as philosophical thought experiments dealing with those issues and often stem from fieldworks in humanly affected places – such as remote locations and in contrast to overcrowded megacities.

The project was jointly funded by Leitrim County Council.